In the early-’90s after graduating college, I moved to Salt Lake City, Utah, seeking mountains, snow, and access to the desert. It couldn’t have been a more disparate topography from the Lowcountry of my youth. For a variety of reasons, I missed my first Thanksgiving and Christmas back in the South, and before I realized it, a year and a half had passed since I had been home. This continues to be my longest contiguous absence from Charleston without at least a visit.

It was within that context that I found myself driving towards the shore of The Great Salt Lake. Despite it being the city’s namesake, folks don’t spend much time at or on the actual lake, which, in stark contrast to our abundant estuaries, supports brine shrimp, algae, and little else. As our car approached the shore, I rolled down the windows, immediately eliciting a chorus of “ewwww” from the other passengers who were dramatically pinching their noses and saying how disgusting it smelled. I, on the other hand, inhaled deeply and proclaimed that it “smelled like home.” Until that precise moment, I hadn’t realized how devoid of scent that place was. Within weeks, I had booked a flight back to Charleston.

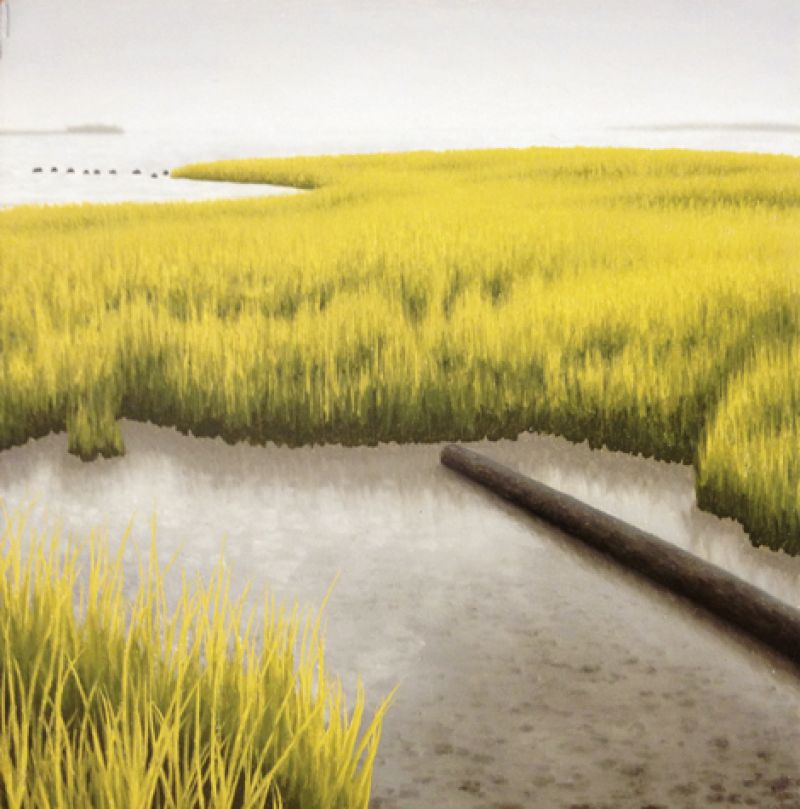

Walking around my native city, I was astounded at the multitude and richness of this olfactory bouillabaisse that ranged from trash to confederate jasmine and a thousand variants in between. Like a blind man granted sight, everything seemed to smell more intense and piquant than ever before. Still, one smell transcended all others—pluff mud. It is the mother sauce of all things Lowcountry. A fecund base from which the bounty of the marsh springs forth to generate the ecosystem that makes this place unique. It emits a fragrance described as either repulsive or nostalgic depending on your point of view. Like most complex Southern things, there is a distinct duality in the personal interpretation.

Pluff mud or “plough mud,” depending on the century of your birth, is an oozy, viscous, dark-brown miasma. The origin and the accompanying smell is the rare confluence of abundant life and death. Our humble pluff is not as celebrated as the sticky effluence produced by the Mississippi River. Certainly, it is just as integral and sustaining to this region as Mississippi mud is to the fertility of the Delta.

According to legend, the mud was used to fertilize cotton fields that had become depleted of nutrients. This garnered the alternate spelling of “plough.” Others contend that the name was born of onomatopoeia, imitating the sound it emits when stepped into. Regardless of the true etymology, it is one of those words that just feels good coming off the tongue. It’s plain fun to say.

Pluff mud has a vacuum-induced sucking power that would make James Dyson envious. You can’t really call yourself a Charlestonian until you have sacrificed a shoe or two to its gooey, vise-like clutch. The constancy of the mud vacillates wildly over the course of a few feet. Within a single step, ankle deep can become mid thigh or worse. Like quicksand, pluff mud draws you deeper the more you struggle.

Pluff mud is generated mostly from decaying spartina grasses, and the smell from the anaerobic bacteria devouring it. However, it also contains the decaying material from all of the life it helps support—fish, crabs, shrimp, dinoflagellates, all live in those marshy environs before becoming pluff mud themselves.

Lowcountry waters aren’t as clear and our beaches not as white as our brethren in Florida due in large part to the pluff mud and spartina grass. I’ve always contended that this was representative of how this place is real versus the ersatz culture below the St. Mary’s River. Maybe that is a stretch or considered another example of “rice bird” elitism. Regardless, the cloudiness of our rivers and sea is the result of the nutrient-rich ecosystem and a mysterious portent of what lies below the surface. Of course, pluff mud forms the root bed for our favorite succulent and beloved bivalves. Harvesting oysters from their muddy perches becomes a tug-of-war between man and mud. To the winner goes the briny spoils.

My mother was a pluff mudder to her core. Her last e-mail address was rmpluffmud@hotmail.com. It’s still in my contacts even though she’s been gone for almost nine years. She loved the creeks, built boats, and was never afraid to get a little mud between her toes. Part of her is in the composition of the pluff mud, too. Commuting home each day, I cross the causeway heading to Sullivan’s Island, and the aroma of pluff mud hits me. The smell of home indeed.

Lowcountry native Buff Ross founded Alloneword Design, which specializes in creating websites for artists, museums, and cultural organizations, as well as other clients. His life is littered with a rangy collection of other occupations, including roofer, painter, associate professor, cook, ship worker, fishmonger, potter’s assistant, archeologist, and budding restaurateur.

Lowcountry native Buff Ross founded Alloneword Design, which specializes in creating websites for artists, museums, and cultural organizations, as well as other clients. His life is littered with a rangy collection of other occupations, including roofer, painter, associate professor, cook, ship worker, fishmonger, potter’s assistant, archeologist, and budding restaurateur.