Early in my life, when I was still in kindergarten, I got some pretty weird ideas about Charleston’s houses. These ideas were planted by my mother one afternoon when we were sitting on the porch of my grandmother’s house, where we’d been living for several years. From the porch we had a view of Church Street and the brick pavement under which there was said to be a pirate’s tunnel to the harbor. Across the street was the house where firemen had once come to rescue the bad girl who’d climbed out a dormer window onto her roof and refused to go back in. Next door was the house where on a summer evening I’d seen the preacher’s daughter emerge in her satin wedding dress and board the horse-drawn carriage for a ride to the church and the start of her married life.

My mother had majored in the history of architecture. She often said Charleston houses were different from those in other cities, and now she was describing the house we’d lived in when I was a baby—a carriage house, she said, with only one story, while Nanny’s was a single house with three stories. I envisioned the old house with carriages in the living room, and I tried to figure out how it was possible to live in anything but a single house.

But what intrigued me most was the other thing: What were the three stories of my grandmother’s house? Maybe she meant our story, and the story of my grandmother before that, and then possibly a third story about an earlier family that we didn’t even know. That third story was the one I was drawn to. I made up a number of versions before finally asking my mother.

“What’s the third story of this house?” I asked.

“Why, that’s where you and your sister live! Up in the garret like artists.”

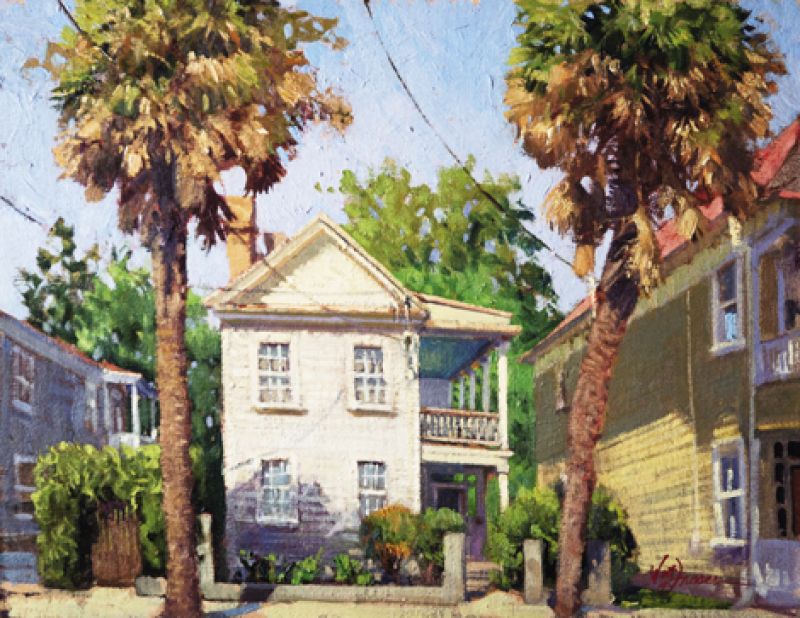

She set me straight, but the idea was already fixed. From then on, I thought of Charleston houses as repositories, holding stories that could be recreated from little hints the houses gave. A girl crying on the roof, a brave bride setting forth. Snatches of conversation overheard, old rumors of scandal, scars of war on the façades.

By the time I was 10, I knew dozens of Charleston houses intimately. Children were free to roam the city in the 1950s, and the doors of my friends and relatives were always open. It was helpful that a lot of these houses were pretty much the same, on Charleston’s unique “single house” plan. You could find your way around easily, and you knew there’d be a powder room under the staircase. But I actually preferred other floor plans that weren’t the same as mine. Two of my friends had tiny one-story houses, a third a dilapidated gingerbread cottage with porches on the back. Another lived in a cavernous mansion on Montagu Street, where the third story had people-size cages built along the walls under the eaves. I never found out what they were for, but dramatic scenarios came to mind.

The city at that time also had a number of abandoned houses, and my friends and I were not deterred by signs or fences. My favorite empty house was only two blocks away. We sneaked in and roamed the rooms, preferably after dark when there could be ghosts, when stories might drift through, hoping to be heard. Who were the abandoners, what had gone wrong? What was in the locked trunk in the corner? Most mysterious of all were the houses I never entered, the homes of black Charlestonians. Half the city was an undiscovered realm, with stories I was determined to know one day.

Freud said houses were often female symbols, both in dreams and in literature. And I thought of old Sigmund when the members of a men’s book club in Charleston told me they would never buy a book that had a house pictured on its cover (as did the novel of mine they were reading). But I believe houses are symbols of family, people who live together, with all their secrets and crimes, their love and anger, their transformations.

And in peninsular Charleston, maybe what had the most lasting effect on me was not the design or the historic past of these structures, but their closeness to each other. We were cheek by jowl in a village, neighbors in the most literal sense, a story collection, a family of families. These days I think often of those two girls on Church Street, the troubled teenager and the bride on the verge of her future. In reality I know almost nothing else about them, what became of them, what other houses they went to. But they have stayed with me for years and years and have shown up, disguised, in every book I’ve written.

Award-winning novelist Josephine Humphreys splits her time between Sullivan’s and John’s islands with her husband, Tom, and standard poodle, Archie.

Award-winning novelist Josephine Humphreys splits her time between Sullivan’s and John’s islands with her husband, Tom, and standard poodle, Archie.