Meet the genius, ambassador, advocate, and Lowcountry legend whose many titles and accolades reflect more than half a century dedicated to elevating the art of sweetgrass basketmaking

Winnowing: the process of separating seed from chaff. For centuries, winnowing in rice fields was done by hand, or rather, by the hands of enslaved people from West Africa, whose strength, sweat, and skills made South Carolina wealthy. But before the actual winnowing, those hands first made winnowing (or “fanner”) baskets from bulrush and marsh grasses. Sturdy baskets in which to shake just-harvested rice hulls to remove chaff from the desired nugget of Carolina gold. Work baskets from working hands. Hands like Mary Jackson’s—strong, proud, nimble, and marvelously skilled. Hands that winnow in their own way, separating fine art from craftsmanship.

“My inspiration comes from what was done before and evolves from old forms, like the traditional rice basket, which is a wide plate with a raised edge,” says Jackson, now 74. The Mount Pleasant native grew up in the Seven Mile area, where she learned basket-making from her mother, Evelyina Foreman, and both grandmothers, Irene Foreman and Estelle Rouse. “I took that [fanner basket] form and had the idea of creating a cover by bending the grass over it and leaving an opening in the middle, and it becomes a wall hanging,” she says, pointing modestly to a large poster in her sun-lit Red Top studio, not far from her John’s Island home.

The poster features a smiling Jackson standing beside said wall hanging; at 42-inches in diameter, it’s her largest piece to date—a Goliath of impeccable sweetgrass sewing. From a distance, this piece resembles a large eye with lashes sweeping dramatically off to the right, where Jackson has left long strands of grass trailing out of the form, as if it’s winking and wondering, “What next? Where can you take me now?” An eye, like that of its creator, that envisions possibilities beyond what others see. An eye willing to follow where the imagination leads.

This stunning piece testifies to both Jackson’s artistry and wry humor. She titled it Never Again—her sentiment after working a solid three years to create it, row by row, stitch by Sabal palmetto stitch. Or perhaps Jackson’s “never again” refers to the slave labor her ancestors endured—the unfinished strands of sweetgrass suggesting freedom, uncoiled and unencumbered. It’s hard to know; she’s a bit of an enigma. One gets the sense that Mary Jackson is a woman of many layers and much depth, a solidity reflected in the gravitas of her baskets. She is modest and reserved, but when she talks her deep voice is gentle, resonant with wisdom and confidence. A woman of few words, she’s content to let her art work speak for itself.

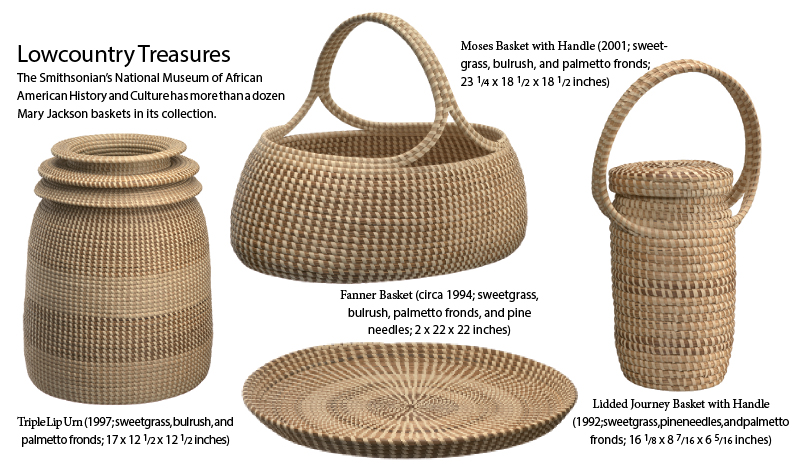

And speak it does, especially to collectors, craft experts, museum directors, and scholars who have been paying attention to Jackson’s work for the last three-and-a-half decades. “Mary Jackson may well be the best known artist from South Carolina,” says Angela Mack, executive director and chief curator of the Gibbes Museum of Art, where Never Again is displayed on a wall bearing her name. The Mary Jackson Gallery houses the museum’s modern and contemporary collections. In addition to the Gibbes, Jackson’s baskets are in major public and private collections across the world, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Museum of African American History in Detroit, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC. They’ve been exhibited at the Vatican and the White House, the Museum of Arts and Design in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, among many others. The Prince of Wales is the proud owner of a Jackson basket, as is the Emperor of Japan.

Jackson received a $25,000 National Endowment for the Arts Heritage Fellowship, the nation’s highest honor in the folk and traditional arts, and in 2008, was named a MacArthur Fellow, though she admits that getting an out-of-the-blue phone call notifying her of the “Genius award” and its accompanying $500,000 prize still feels surreal. It’s certainly a long way from a four-year-old girl, the second oldest of 10 children, learning to sew sweetgrass at her mother’s and grandmothers’ knees.

Take Off: Mary Jackson, pictured in 1984 with baskets headed for the collection at the Charleston International Airport; it proved to be a pivotal year in her career, as the Gibbes Museum of Art hosted a solo show of her work and she exhibited her baskets at the highly selective Smithsonian Craft Show.

Ancient & Contemporary

It’s both a long way, and not long at all. Jackson’s technique and process are exactly the same as her mother’s and grandmothers’, and the same, too, as her older sister who sold baskets downtown at the Market, and as their West African ancestors who made agricultural and household baskets out of similar indigenous materials 300 years ago. “It was a chore; making baskets was something we were expected to do in the summer,” says Jackson. She recalls hot days sitting under her grandmother Foreman’s tree with her cousins. “We had fun competing to see who could make the best one.” Then as now, the process for a sweetgrass basket-sewer, even one as accomplished as Jackson, involves harvesting grass from dunes and marshes; drying it; gathering pine needles and bulrush, if mixing in darker colors; and manually tearing strips of palmetto fronds—and if you’re Mary Jackson, doing so with exacting care.

Starting from a single knot, Jackson meticulously selects only the best sweetgrass and begins to tightly coil the fibers, binding them—with painstaking precision—with palmetto strips, and then continuously feeding grasses into the coil. There are no shortcuts (though Jackson’s husband, Stoney, a basketmaker in his own right, does harvest her grass), just tedious, slow, hard work, and long days in her studio, with CNN and the whoosh of traffic along Highway 17-South keeping her company. Jackson typically juggles several pieces at a time, including some at her home studio, where she’s prone to work late into the night.

“This one I think I started eight years ago,” she says, reaching down to her studio table to pick up a flat, plate-sized bit of perfection and potential. Perhaps it will become a cobra basket—tall and sensual—or maybe a version of Two Lips, one of her favorite invented forms, inspired by an old spittoon. She has considered revisiting another finished basket along the studio’s back wall: “I think I might build it up some more and do a different edge on top, make it more like an urn,” she says.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Jackson’s mother, grandmother Irene, and other Mount Pleasant basketmakers peddled their wares along what was a still-rural Highway 17, selling baskets for 10 to 15 bucks a pop. “And that price was for a beautiful, mid-size, complicated basket,” Jackson notes, recognizing even as a child that the price undervalued the skill and time involved. “I always told them ‘I’m not going to give away my baskets—it’s too much work!’” (Today, a Jackson commission commands, shall we say, a good bit more.) But neither did she ever imagine she’d be a full-time basketmaker.

After high school, Jackson moved to New York, attended business school at night, and spent a decade working in secretarial and administrative fields, exploring museums and galleries in her spare time. She was particularly drawn to contemporary art, which, she says, inspired her to try making “forms and sculpture-like baskets that had never been done before.”

Jackson returned to Charleston in 1972, met Stoney, married, and worked in the MUSC biochemistry department for a stint, until their son was born and diagnosed with chronic asthma. She left MUSC to care for him, “and that’s when I went back into basketry,” she says. From the get-go, Jackson says, she worked to “master the technique and traditional forms so I could then take it to a level that I felt was more artful.”

One & Done: Commissioned by a patron who later donated it to the Gibbes, Jackson’s Never Again (2007, sweetgrass and palmetto, 42 inches) took three years of intricate work. A masterpiece of craft, the shape harkens back to the traditional flat rice baskets, but takes it to a soaring new level.

Elevating & Advocating for the Art Form

What distinguishes her elegant baskets are both her refined hand and her expressive, unique, and challenging designs. According to art collector and Jackson’s friend and patron David Rawle, “Mary’s baskets are solidly grounded in historic shapes that she has endowed with great strength and monumentality. They are both regal and sublime. Like great sculpture, Mary Jackson baskets beg to be touched.”

“Mary has created museum-worthy pieces by taking this fabulous tradition and developed it to the point where her skill as an artist is recognized around the world,” says Gibbes executive director Angela Mack. In 1984, the museum helped launch Jackson’s career and remains to date the only institution in the country that has given her a solo exhibit. “Mary’s work stands apart because of her dedication, her goal for perfection, and her creativity,” Mack adds. “She’s married to these traditional forms but takes them to a monumental level.”

But that’s far from Jackson’s only contribution. In the mid 1970s, she began addressing issues of sweetgrass scarcity. Native habitats were becoming increasingly threatened by coastal development and the proliferation of resort and gated communities, so she worked to help basketmakers find accessible places to gather their material, including negotiated harvesting agreements with the then-owner of Kiawah Island. Jackson also worked with Clemson Extension horticulturists to propagate new varieties and plant sweetgrass in places such as the Alcoa plant near Mount Holly and Charles Towne Landing, where basketmakers were welcomed to harvest.

In 1988, she cofounded the Mount Pleasant Sweetgrass Basketmakers’ Association to support the artisans and help promote and preserve the tradition. For 10 years, Jackson was heavily involved in advocating for this cultural and ancestral craft, all while taking it to new levels, far beyond its humble utilitarian origins. “Mary really rose to the occasion as a community leader, both outspoken and effective,” says scholar and basket authority Dale Rosengarten. She first got to know Jackson in the early 1980s while researching “Row Upon Row” for the McKissick Museum, a 1986 exhibition and later a book, the title of which came from the basket-sewers themselves. In 1989, in the wake of Hurricane Hugo, Jackson traveled to Washington as association president to solicit disaster aid to help rebuild the basket stands.

Slowing Down & Popping Up

Jackson’s efforts to master, honor, preserve, and advance the craft of her ancestors have paid off. In the same year that she received the MacArthur Genius grant, Jackson was honored with the Environmental Stewardship Award of Achievement given by the South Carolina Aquarium. But more importantly to Jackson, her fellow basketmakers also seem to be thriving. According to Rosengarten, today there are an estimated 300 families—some 1,000 individuals—actively involved in the sweetgrass basket industry, though, she adds, the numbers are hard to quantify.

In a culture where smartphones and apps rule, this old-world technology of coiling a basket from nothing but plucked grass, patience, and calloused fingers is still viable and valued, disruptive in its own throw-back way. Think of the basket stands that once lined Highway 17 and those that still dot it—an early iteration of Etsy, a highly innovative, direct-to-market platform. With a deep appreciation of where the tradition rises from and an artist’s vision for where it might yet rise to, Jackson has been an inspired innovator of this age-old craft. So it’s fitting, perhaps, that her baskets will be part of that more recent trend—a pop-up gallery—during Spoleto Festival USA this spring. “It’ll be a new experience for me. I think it will be fun,” says Jackson.

Jackson’s work ethic remains impressive, yet given her arthritic hands and slowed mobility post-spine surgery a few years ago, she’s ready to taper back a bit and “spend more time with my three granddaughters,” she says. She still travels to the annual Smithsonian Craft Show, a highly competitive juried exhibition in April, where she enjoys catching up with her artist friends from across the country, “but I’m not traveling for shows or speaking engagements as much as I used to.” Thus the pop-up exhibit this May (see sidebar below) in Theodora Park across from the Galliard is exactly her speed. Plus, says David Rawle, the event’s organizer, “It’s a wonderful opportunity to see and appreciate artwork that is from nature in a beautiful natural setting.”

Passersby can visit with the artist, view some of her favorite designs, and get a first-hand feel for the absolute authenticity that is Mary Jackson. “There’s not a phony bone in her body, and the same with Stoney,” says Rawle. “She’s genuinely interested in and respectful of other artists’ work and ideas. She’s extraordinary, the whole package—a humble and generous woman. You can see her integrity in her work, her soul in every coil.”

Jackson’s baskets may not hold rice, but they carry forth substance indeed—the timeless hand-wrought beauty of tradition and the bold reimagining of how to embrace and elevate that in contemporary, relevant ways.

A Basket Full

Sweetgrass may only grow in a very specific and limited coastal habitat, but thanks, in large part, to Mary Jackson’s leadership and artistry, the art and craft of sweetgrass basketmaking is known and admired the world over. Among her numerous awards and accolades, Jackson has been honored by the following:

2018: Elected to the American Craft Council College of Fellows and was one of eight recipients of the 2018 American Craft Awards, which honors artists who’ve made an outstanding contribution to the crafts in America.

2016: Gibbes Museum of Art opened a new modern and contemporary art gallery named permanently in Jackson’s honor.

2009: Received an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from the College of Charleston.

2008: Given the SC Aquarium’s Environmental Stewardship Award of Achievement.

2008: Named a MacArthur Fellow, often called the “genius grant.”

2000: Jackson’s work was part of Five Women in Crafts at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery, which heralded her as “a consummate designer and superb craftswoman.”

1993: Given the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ Lifetime Achievement Award.

1988: Cofounded the Mount Pleasant Sweetgrass Basketmakers’ Association.

1984: Her first solo exhibit at the Gibbes Museum of Art introduced Jackson to the broader public. Also that year, she was invited to present her baskets at the Smithsonian Craft Show, another career turning point.

Pop-up Exhibition

May 24 & 25

View an array of Mary Jackson baskets on loan from private collections at Theodora Park. A reception with the artist will be held May 25 from noon to 2 p.m. Theodora Park, Anson & George Sts. - Friday & Saturday, 10 a.m.-7 p.m. Free & open to the public. Workshop at the Gibbes

May 29

Join Mary Jackson in the Gibbes studio for a demonstration and discussion of her process. Gibbes Museum of Art, 135 Meeting St. Wednesday, 10-11:30 a.m. $15; $10 member (includes admission) (843) 722-2706, gibbesmuseum.org

Photographs (two lips basket from a private collection) by Aleece Kingsley-Taylor & (Portrait) Peter Frank Edwards; Photograph courtesy of Special Collections, College of Charleston; Photographs by (materials) Peter Frank Edwards & (Jackson exhibit) Jennifer Gerardi, Courtesy of Craft in America; Photographs (7) by Jack Alterman; Photograph by David Rawle