Get to know Charleston’s most popular barrier island beaches

Absence, they say, makes the heart grow fonder. That was surely true for many Lowcountry residents who longed to feel sand between their toes or to take deep inhales of salty air rolling off an incoming tide, while our beaches were closed during COVID-19 precaution days. But now that the Atlantic beckons and our wide beaches are once again open for the serious business of sitting back and soaking up some sun, it’s time to face the age-old question: which island to visit?

Your destination of choice may be a matter of habit or family tradition, or it might just depend on your mood. Folly, Sullivan’s, and the Isle of Palms all share the same basic genes: barrier islands on the same blue sea; but like siblings, each has a distinct personality. If Charleston proper is the revered grandmother—the geographic grande dame of these environs—and Mount Pleasant and West Ashley are the parents—the bill-paying folks with carpools and grocery lists—then the islands are three sisters—the fun-in-the-sun, much-loved gals. Read on to get to know their backgrounds and discover where you might want to park your beach blanket.

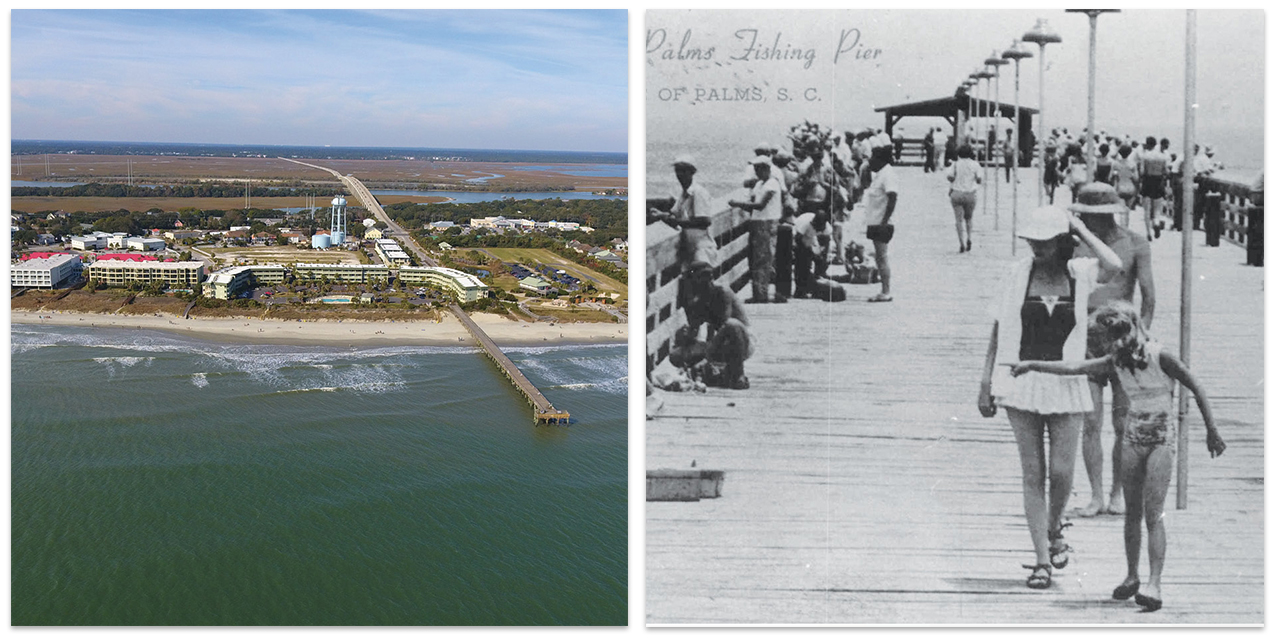

(Left) Front Beach Isle of Palms and the pier in 2017; (right) Folly Beach fishing pier, circa 1960s

Gregarious & Spunky Isle of Palms

Since all three barrier islands are roughly 25,000 years old, birth-order generalizations don’t necessarily hold sway. But if we didn’t know the geology, the Isle of Palms could pass for the older, more responsible kid; the one who’s conscientious and eager to please, who does her homework with care but then goes out to play—and plays hard. She’s a balanced island, tolerating a fairly even mix of residents and tourists, of very big houses and some not so big. Gregarious and athletic (she loves beach volleyball!), sister IOP is committed to having a good time—but it’s good clean family fun.

Stretching from Dewees Inlet to Breach Inlet, Isle of Palms is a long-legged gal, with more than six miles of wide, relatively quiet, and clean beachfront. In fact, IOP was the first beach in the state to have earned the Clean Beach Council’s “Blue Wave Beach” award, the saltwater equivalent of the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. Originally called “Hunting Island” and later “Long Island,” she has been home to Sewee Indians, British troops, and the occasional pirate or two. Seasonal residents and visitors began traveling to the island in the late 19th century, around the time it was bought by Dr. Joseph Lawrence of Beaufort, president of the Charleston and Seashore Railroad Company. Renaming her Isle of Palms, Lawrence worked to improve the steam ferry service from Charleston to Mount Pleasant and to establish electric streetcar lines from Mount Pleasant over the Cove and Breach inlets, leading to the eventual development of the island. By 1906, the 50-room Seashore Hotel was built near what is now known as Front Beach IOP. A dance pavilion and Ferris wheel soon followed, and the Isle of Palms became an East Coast hot spot. Folks from as far away as Augusta and Savannah chartered trains to come and see her.

Throughout the late 1940s and ’50s, the Isle of Palms began a growth spurt that has only recently subsided. Her seaside amusements—which by then included three beachfront pavilions as well as the longest fishing pier in the Carolinas at the time—continued to draw crowds, while her new owner, J.C. Long of the Beach Company, attracted many permanent residents with low-cost housing for World War II vets. The island soon matured into the well-rounded gal she is today—part bedroom community (with ocean view!) and part summertime playground with fun and frivolous tourist attractions.

Memories of IOP:

The late Kathryn Carroll, who died in 2009 after living on the island for 50 years, fondly remembered the early days, before there were even houses on the ocean side of Ocean Boulevard, let alone Wild Dunes. “The Red & White grocery had just opened the week we arrived. The island was small and friendly; a perfect place to raise a family—kids could safely roam wherever they wanted. Nobody locked their door, even when they went on vacation,” Carroll recalled. Her family immediately felt welcomed into the community, she noted: they arrived in August, and by October, before she’d barely had a chance to get her feet sandy, Carroll belonged to the Ladies Playground Auxiliary.

Hurricane Hugo and the Isle of Palms Connector changed much of the atmosphere, according to Carroll, whose family has been in the island real estate rental business for 30 years, and whose son Jimmy is now raising his family on the Isle of Palms. “We’re much more sophisticated than we used to be. I miss the quiet and the empty, undeveloped space that we had when we first arrived,” Carroll said, “but there’s still very much a sense of community, and you can’t find a nicer beach anywhere. I wouldn’t live any place else.”

Know Before You Go: The Isle of Palms has reopened to the public, but as of press time, the municipality is prohibiting gatherings of more than three people, except family members who live in the same household. For up-to-date info, visit iop.net.

(Left) Marguerite Strickland Stith with son Paul, circa 1950; (right) The southern tip of Sullivan's near Fort Moultrie curves to the Intracoastal Waterway, with Mount Pleasant's Old Village on the far side. There, a trolley bridge across Cove Inlet once connected summer residents to the island.

Low Key & Traditional Sullivan’s Island

Sullivan’s is pretty tight with her big sister IOP; they share the same elementary school, an inlet, some traffic, and bridges if they wish. But Sullivan’s Island is the more low-key gal, the one who, though equally warm and personable, sticks a little closer to home. She’s well-mannered and well-groomed, a bit more traditional and reserved. Like the boxy lighthouse on her shore, she’s dependable and serene, the sibling you go to when you need a long walk, good conversation, and a cold Irish stout from Dunleavy’s to set the world right.

Sullivan’s has always been the protective sister. Named for Captain Florence O’Sullivan—an early Irish Catholic settler who placed a cannon at the island’s tip to warn Charles Towne of danger—she still has a bit of military brat mixed in with her refined salty charm. Bunkers tucked about the island are reminders of her past military glory; one even houses the small public library. Revolutionary war hero Colonel William Moultrie became her first marketing mascot, as “Moultrieville” evolved into one of the most popular “resorts” in the nation from the mid-1800s until the Civil War.

Pretty and petite (at a little over two miles, her beach is a good jog long), Sullivan’s today is more than merely attractive. She has depth of character; layers that lie in her soft and inviting sand. There’s her loyalty to generations of families who have sought her summer solace, but there’s also an unsettling history. Sister Sullivan’s past includes serving as a quarantine way station for ships importing Africans to Charleston during the Atlantic slave trade, and home to pest houses where human “cargo” were held before being sold into slavery.

Today, the pest houses are long gone, and so too are many of Sullivan’s original humble beach cottages. In their place, huge post-Hugo homes dominate the beachfront, but there are still no condos or hotels. Though affluent, she remains homey and welcoming. She’s the kind of beach where holiday lights on the fire station are over the top; where the kid who wins the annual Golf Cart Parade for the second year in a row gives his prize to the runner-up; and where the Volunteer Fire Department’s fish fry shack is the place to be and be seen.

Memories of Sullivan’s:

Eleanor Condon Ilderton of High Point, North Carolina, has trekked to Sullivan’s Island for more than 70 summers. Born and raised in Charleston, she began visiting her grandparents, both sets of whom had homes on Sullivan’s, “back when you had to take the ferry to Mount Pleasant and then the trolley car.” From the time she was 11, when her father built a house on the island, her family would close up their Hampton Park home the day after school let out and move to Sullivan’s until Labor Day.

“The island was a great place to be a teenager,” Ilderton recalls. “Charleston boys would come for dances at the Isle of Palms Pavilion—several would hide in the car trunk, since it cost money to cross the “new” bridge. We’d dance at The Breakers (on Middle Street by Station 22) where there were always boys from the College of Charleston and the Citadel. Once, while my parents were on a trip, we had full reign of an old Ford. We’d pay 75 cents to fill her up and drive all over the island and dunes until it ran out. Then we’d walk to the gas station and fill her back up.” Memories of the “Vegetable Man” with his old delivery truck, the movie house at Fort Moultrie, and the taste of artesian water in the spigots are still vivid to Ilderton, who brought her own crew of nine children to the island every summer from North Carolina. Her son Pat lives on Sullivan’s; his office is where The Breakers once stood, where his mother once danced her summer nights away.

Know Before You Go: As of press time, the beach is open to the public for exercise only, with social distancing requirements in place. For up-to-date info, visit sullivansisland.sc.gov.

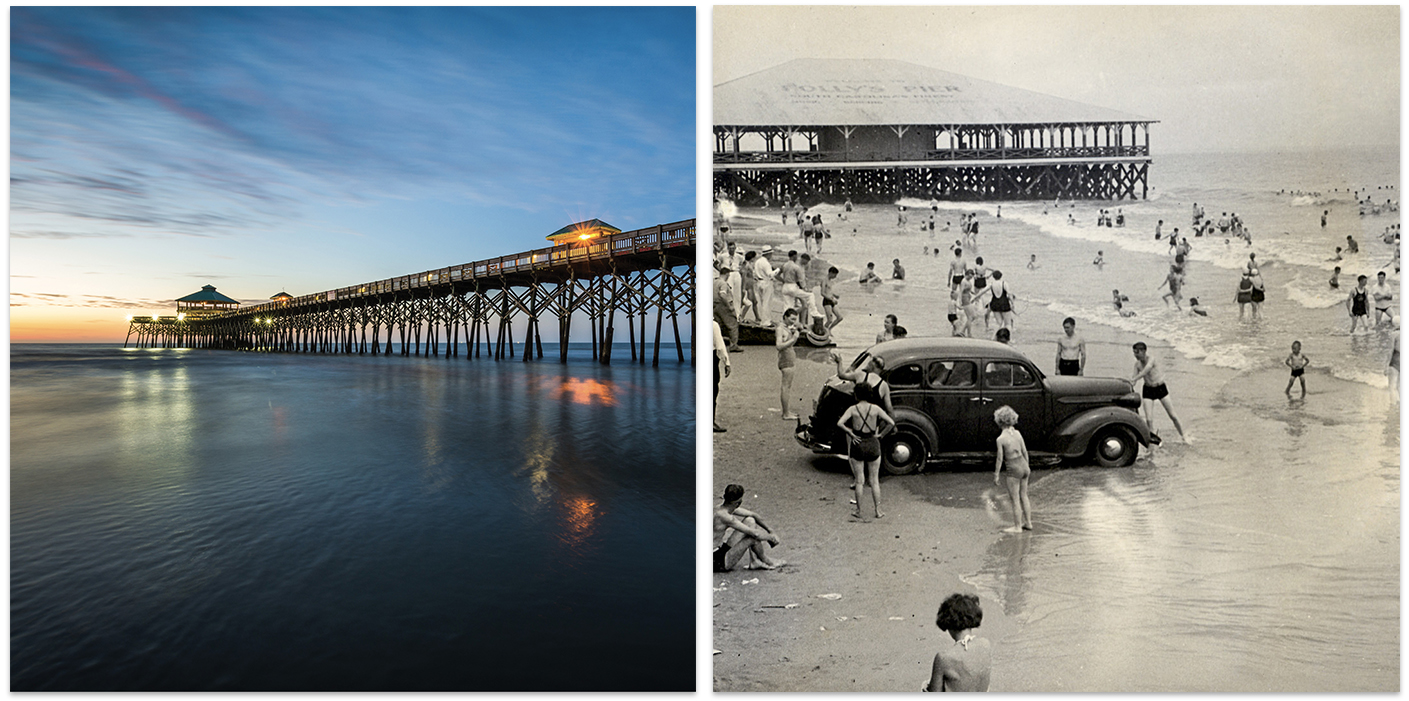

(Left) While there are plans to replace the 1,045-foot Edwin S. Taylor Fishing Pier, which opened on July 4, 1995, it will remain open to the public through the summer season. (Right) A car parked on the beach gets caught in the incoming tide, circa 1950.

Fun & Carefree Folly Beach

Folly wears her name well. She’s the unpredictable, carefree sister—the one who stays out late, throws caution to the sea breeze, and errs on the side of fun. The word “folly” is derived from the Old English for “dense foliage,” yet the more popular definition equally applies to her contemporary landscape. She’s eclectic, whimsical, and endearingly adolescent. She doesn’t mind being a little rough around the edges there on the “Edge of America,” where her waves are big, her beach is wide, and her warmth is genuine.

Little is known about her pre-Civil War days. Early maps show that Folly was once called “Coffin Land,” possibly because ships would often leave plague or cholera victims on barrier islands before approaching a large port. By 1861, however, the island housed a massive tent city of Union soldiers planning the siege of Charleston. Nearby Morris Island saw heavy fighting, including the ill-fated attack by the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. After the war, Folly fell from the limelight. Travel to the island was difficult, with only one meandering dirt road cleared. A popular and fittingly Folly-ish phrase of the day was “Be independent, make your own rut.”

The island flourished in the post-war glee of the Roaring Twenties. The Folly Beach Corporation began developing the island, advertising that it was “45 minutes from Broad Street,” though in reality it could take up to two hours. In 1920, they sold 214 lots, with a front beach lot going for $2,000. Buses began service to the island, and the steamer Attaquin made a two-hour trip to Folly down the Stono, costing one dollar round-trip. Folly Beach was all the things her sister islands were not: available, affordable, and relatively accessible. With the Atlantic Boardwalk that included the Folly Pier and Pavilion and a seasonal amusement ride area, Folly was the place for fun, and more than 200,000 people visited her in 1925.

While hard economic times, the toll of a toll road, and a 1940 hurricane put a temporary damper on Folly’s growth, after World War II she began booming again. Even during her heydays in the ’20s and later in the ’50s and ’60s, she has happily been the down-home beach. Comfortable in her own skin, Folly’s got nothing to prove.

Memories of Folly Beach:

Diversity has always been one of Folly’s strong points, according to Paul Chrysostom, owner of Mr. John’s Beach Store, a Center Street landmark since 1951. “Folly is very accepting; you can be a little odd here,” Chrysostom says. “We have hippies and bikers, doctors and lawyers, college students and young families. The eclecticness adds layers, it adds realness.”

Paul’s father, the eponymous Mr. John, began the store as a seasonal business. His wife was a pharmacist, and they sold the typical array of beach toys and floats, had an old-fashioned soda fountain, and sold prescriptions. They lived above the store, where Paul now resides. Mr. John’s is open year-round these days, but it’s still a mom-and-pop shop. There’s no price scanner at the checkout, nor much rhyme or reason as to what you might find where. It’s a microcosm of Folly, a fascinating mishmash of stuff, from practical to off-the-wall. “We have customers whose grandparents brought them here when they were kids,” he says. “One summer, we chatted with a family celebrating their 50th Fourth of July on Folly. There’s a sense of connection here. Folly gets in your blood.”

Know Before You Go: As of press time, Folly Beach is open to the public, with social distancing requirements in place. For up-to-date information, visit cityoffollybeach.com.

Photographs courtesy Christian Hinkle, The Charleston Museum, George A. Kenna, Reedy River Drone Company, Jimmy Creech, Robert Knight, Alyssa Stubblefield