Find out what Read is working on for his solo exhibit at the George Gallery this fall

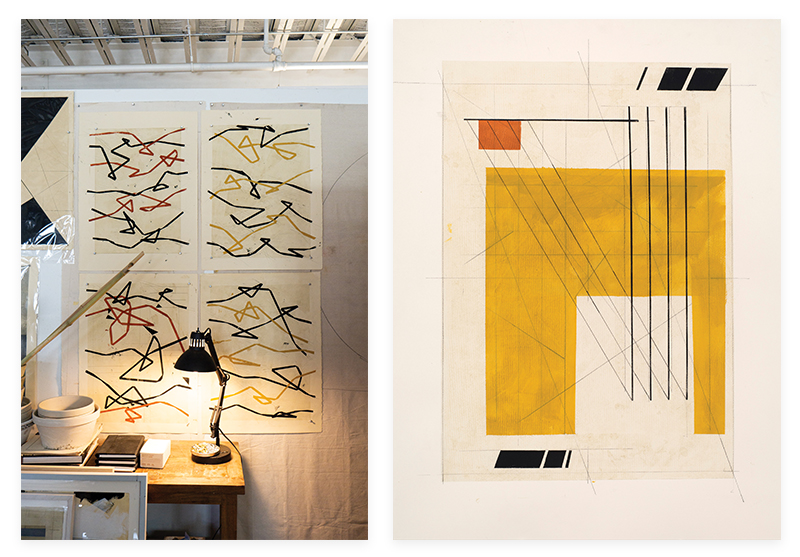

George Read displays Architectura (mineral pigments and graphite on Arches paper, 30 x 22 inches, 2022).

George Read’s paintings indicate a masterful eye for space and contrast. His crisp, clean lines and repetition create soothing visual rhythms; his palette is restrained and intelligent. While everything else is tidy, drips of pigment, pencil lines, and the occasional thumbprint reveal the hand of the artist. Read uses unusual materials, such as black Flashe paint that has a deeply saturated matte finish, air-dried Arches paper, and hand-mixed mineral pigments. His career has been about details, so it’s no surprise that the details define his work.

He hasn’t always been an artist. While studying Harvard’s pre-med curriculum, Read took a required humanities class and fell in love with art history. He was tutored by Spanish sculptor Eduardo Chillida and graduated with a history of art degree. That summer, Read worked as art critic Harold Rosenberg’s gardener in the Hamptons and did chores for abstract expressionist artists Willem de Kooning and Adolph Gottlieb before decamping to Italy for more study.

On Read’s way back to the US, he had a show in Paris with Japanese sculptor Tetsuo Harada, which caught the attention of art critic Michel Tapie, who invited Read to share studio space in the new Le Centre Pompidou. Before Read could move in, Sotheby’s in New York City offered him a job as the assistant to the head of French furniture. Here, Read shares his artistic journey and what he’s working on for his solo exhibition at the George Gallery in October.

(Left) Lido series (mineral pigments, Flashe black, and graphite wash on Arches paper, 30 x 22 inches each, 2024) at his studio; (right) Riviera.vi (mineral pigments, Flashe black, graphite, and wash on Arches paper, 30 x 22 inches, 2024)

Art Education: I studied Rembrandts in the morning and then spent time in the studio at [Harvard’s] Fogg Museum, where we were encouraged to explore techniques. It was hard, but it was nothing like my first year at Sotheby’s.

Working at Sotheby’s: A friend knew I needed a job, so he introduced me as a specialist in French furniture, which I wasn’t. When they offered me the job, I thought, “It’s furniture. How hard can it be?” I spent a few months memorizing everything in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, so I felt pretty confident. Then, I arrived at an international auction house where the standards are rigorous and mistakes are very public. Everything I was hired to look at wasn’t in the books. My first week was spent at a warehouse in Harlem with an assistant and an IBM typewriter cataloging a sale. The assistant typed verbatim so whatever I said was exactly what would be in the catalog. We’d do 200 pieces in a day or two. What I didn’t know quickly became transparent, but people took pity on me. Eventually, I memorized things such as every monarch of Europe and when they reigned because if you don’t know the reign dates, you don’t know what to call the furniture. I went on to be an auctioneer and built a handful of personal clients, including Oprah and Meatloaf. None were in New York, so I moved to Charleston, which my kids thought was great.

Back to the Studio: I was a jock growing up, and in my position on the hockey team, I had to skate backward. It turns out that’s really bad for your hips, so I had to have both replaced. While I was sitting around after rehab, I did some paintings for my business partner, who had just bought a house. Then my daughter-in-law, [Sally King Benedict], who is a very successful artist, gave me a dose of my own advice, which was, “Stop making excuses for not making art. Get a studio at Redux and get busy.” I’m glad I did because I’m surrounded by people who are vibrant and enthusiastic, and they’ve given me great advice.

Finding His Style: When I took up painting again, it was minimal, abstract, and edgy. It would never have occurred to me to do something representational. My tutor at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard was Eduardo Chillida. He told us what we were doing was deadly serious, and he was a very serious guy. We didn’t dare crack a joke or a smile. He told us we were exploring the plasticity of color, form, and line on a 2-D surface, and we were supposed to figure out the mystery. He was exploring the limits of defining empty space. I still can’t get away from that. He also told me to work on at least five things at once, and as soon as I feel slightly unsure about where to go, I must work on something else. That’s saved me so much paper and canvas. Knowing when to stop is part of the creation process.

Solo Show: I’m going in a couple of directions right now, but I like the idea of making an installation that works together in an intriguing way. I’d love to create a series of four or six or eight pieces.