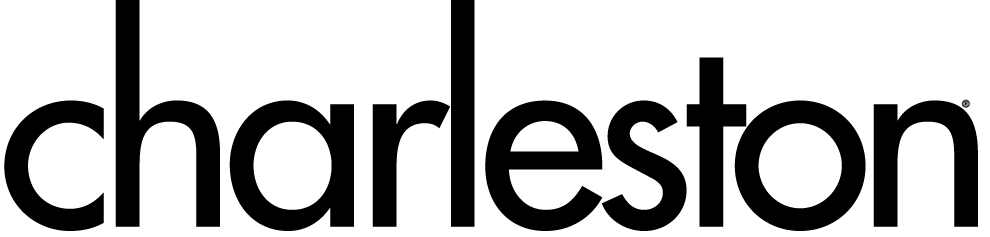

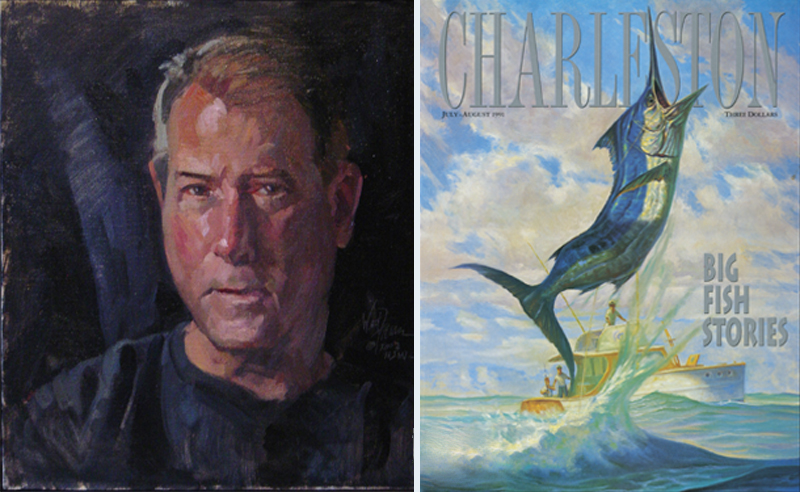

(left) Study of John Doyle by West Fraser, oil on canvas, 16 x 14 inches, circa 2005; (right) John Carroll Doyle’s painting Into the Light on the July-August 1991 cover of Charleston magazine In Memoriam: John Carroll Doyle My friend John did not survive heart surgery. He passed away last week, and I’m certain he’s joined his heroes from the artistic past, such as his favorite, John Singer Sargent. John was truly a creative individual. A self-taught painter and photographer, he produced iconic pieces that reveled in memories and stories of Southern culture, especially of his beloved birthplace, Charleston. He brought back to life the colorful flower ladies, fishmongers, and Mosquito Fleet fishermen, but John’s most popular works were the beautifully designed light- and energy-filled canvasses of billfish and wading birds. John was presented the Order of the Palmetto, the state’s highest citizen honor, and his works graced many covers of sports fishing publications, such as Marlin and Sporting Classics. His dynamic paintings also enhanced numerous restaurants and clubs from Charleston to Chicago, creating a spirit of place. I first met John in 1974 when he was building wooden boats at Cap’n Harry’s Blue Marlin Bar in the old warehouse district at Cumberland and State streets. His watercraft were uniquely beautiful, made with respect for traditions and memories of Charleston’s Mosquito Fleet and the beautiful varnished boats at the old City Yacht Basin—memories that fueled fantasies of world travel that he brought to life in later years through his paintings. At the time, John was larger than life—an artist, boat builder, and popular personality. As John has shared in his autobiography, John Carroll Doyle: Portrait of a Charleston Artist, he struggled with addictions. By the time I moved back to Charleston in the early ’80s, he had sobered up and become a stalwart mentor and sobriety advocate. We became close friends and spent many hours discussing color theory and our favorite artists or pondering the vagaries of the life we had both chosen as artists. In retrospect, I would say that John and I had a 30-year conversation that took place each time we saw each other, picking up were we had left off. John had style—he always dressed nicely, placed beautiful flowers in his studio and home, and surrounded himself with beautiful women. He influenced his surroundings and created beauty in his life at all times. He was especially generous with his gifts to friends and to charities such as Darkness to Light, The Center for the Birds of Prey, and the American Heart Association. As with so many artists, money was not important but absolutely necessary, yet participating selflessly as a community leader, in his own way, is clearly a legacy of John Doyle. During one of our last conversations, John shared with me his desire to leave a legacy of a scholarship for qualified young adults who want to study traditional representational art, an opportunity that he did not have in his youth. I must say that John certainly has given more to Charleston than he ever received; he was that kind of man. In John’s time, Charleston experienced a second renaissance in the arts fueled in part by his work, which will be categorized alongside other important local artists, such as William Aiken Walker, Alice Ravenel Huger Smith, and Elizabeth O’Neill Verner. Yet it’s memories of his sincere kindness, generosity, and spirit of integrity that I will hold most dear. A gathering of friends will be held this evening, Tuesday, November 18, from 5 to 9 p.m. at the John Carroll Doyle Gallery, 125 Church St. A black-tie Celebration of Life will occur in mid-January. To read John Carroll Doyle’s obituary, click here. |