And learn about the local advocates and preservationists who banded together to save the island and its historic light

It’s a forgotten island, an uninhabited outpost at the entrance of Charleston Harbor accessible only by boat and hidden from view by the trees of James Island. Yet the wind that whispers across its eroding shoreline is the voice of history. From Charleston’s earliest beginnings, Morris Island has played a defining and often dramatic role in the Lowcountry story.

Morris Island seems like a quintessential barrier island—long and narrow, fronted by a surf-lined beach with marshland at the rear—but it’s an island in trouble. The erection of jetties in the 1880s to create a central shipping channel into Charleston Harbor altered the currents that have inexorably eaten away its shoreline. Today, it is less than one-quarter of its original size. Consequently, most of the land on which Morris Island’s history took place is now underwater. The most striking evidence of this is the lighthouse, which is an island unto itself, surrounded by Lighthouse Inlet.

Even without human interference, the island has experienced an ever-changing geography. Until the late 1700s, what we know as Morris was actually three separate land masses. At the harbor mouth was Cummings Island, in the center was Morrison’s Island, and on the southern end, forming the largest of the three, was Middle Bay Island. Storms as well as natural wind and wave action eventually molded the trio into one entity. For simplicity’s sake, this article will refer to the original three islands as “Morris Island.”

The Stono, Etiwan, and other early coastal tribes undoubtedly used the island for hunting and fishing. But even after colonization, it was only sparsely settled. With scarce freshwater and scant arable land, the environment was unsuitable for planting. Situated as the gatekeeper of the harbor, however, it witnessed almost every significant event in Charleston from 1670 onward. One of the most noteworthy: in the mid-1860s, the island was the scene of intense and bloody fighting during the Civil War.

Watch a drone video of Morris Island

Coffin Land

There is an inherent sadness when walking the Morris Island beach—a melancholia that seems to permeate its windswept openness. Perhaps it’s the loneliness of the beach, its wildness and isolation. Or, as some attest, perhaps there really is a residual aura that echoes Morris’s tragic history.

That legacy began in September 1700, when vessels carrying Scottish colonists from the failed Darien colony in Panama put in to Charles Towne for repairs. The small flotilla had barely left Panama when they encountered a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico. The storm dismasted their flagship, the Rising Sun, and severely crippled the others. The ships limped into Charles Towne under makeshift rigging and anchored offshore, likely at the deepwater area off Morris known as “Five Fathom Hole.”

While historical accounts vary, most place the number of men, women, and children on the Darien vessels at about 200. All stayed aboard except for a small group that went ashore with Presbyterian minister, Archibald Stobo, who had been invited into town to preach.

Of the many hurricanes to hit Charles Towne, the storm of September 1700 leaves one of the saddest records. The ships were dashed to pieces, and all aboard drowned, their bodies later washing ashore on Morris Island. An account written years later by Charlestonian Louisa Susannah Wells, “The Journal of a Voyage from Charlestown, SC, to London in the Year 1778,” recalled how the dead included “women with their infants clasped to their breasts.” It took an entire day to bury the victims. This heartbreaking experience touched locals so deeply that the island soon became known as “Coffin Land.” It was an apt moniker: The Darien colonists were but the first of many who, over the ensuing centuries, would be buried in the island’s lonely sands.

Beacon to the Sea

In the days of sail, the first introduction to Carolina for those arriving by sea was the white beach of Morris Island. The main shipping channel was then a deepwater trough that began at Lighthouse Inlet and ran parallel to the length of Morris Island all the way to the harbor mouth. Other smaller channels led into the harbor, but they were surrounded by a network of sandbars that shifted with the tides. Even when using the main channel, “crossing the bar” was risky business. Over the years, numerous ships went down in the attempt. Vessels often lay at anchor in Five Fathom Hole for a week or longer while they waited for favorable winds and tides.

An even more basic problem for mariners was locating the main channel. The islands and inlets along the southeastern shoreline look maddeningly alike from sea. To remedy this, in 1672, beacons were placed on Morris Island and its counterpoint on the other side of the harbor, Sullivan’s Island, to guide vessels to port. According to the National Park Service, these first beacons were tallish wooden platforms lit with “fier [sic] balls of pitch” and oakum, a material made from hemp that served as the wick. Placed in an iron basket, they were set afire nightly by a keeper who usually doubled as a coastal watchman.

In 1767, Samuel Cardy, the builder of St. Michael’s Church, was commissioned to erect a brick lighthouse “with a lanthorn [sic] on top” on Middle Bay Island. This first “Charleston Light” was an octagonal tower that stood 42 feet tall. Situated at the southern end of the island, it served both as a beacon signifying the port and as a range marker noting the entrance to the shipping channel.

It was this lighthouse that the Patriots darkened during the Revolutionary War to inhibit British maneuvers when, in December 1775, a fleet of British men-of-war began amassing off Charleston as they prepared to attack Sullivan’s Island. Anchored at Five Fathom Hole, the British made use of their proximity to Morris Island. General William Moultrie states in his Memoirs of the American Revolution that John Morris supplied the British with meat from the cattle he kept on his island. Moultrie also notes that the city’s Council of Safety quickly ordered the livestock removed and the lighthouse extinguished.

Moultrie and his Patriots would win the Battle of Fort Sullivan in June 1776, forcing the British to flee. Yet upon their return in 1780, they emerged victorious. A testimony to the Morris Island light’s importance: one of the first things the British did after taking Charleston was to make the lighthouse operational again.

The onset of the 19th century brought a new lighthouse to Morris Island—a 102-foot-tall tower with a revolving beacon that could be seen 12 miles out to sea. At this time, Morris Island served as the site of the town’s lazaretto, a quarantine station more commonly referred to as a “pest house.” Quarantine was the first defense against the importation of virulent diseases such as smallpox, yellow fever, and cholera. Sadly, not everyone quarantined survived, and those who died were buried on the island in a potter’s field.

With the advent of the Civil War, Morris Island’s location at the harbor entrance made it one of the most strategically important sites for the Confederacy. By 1863, two fortifications had been erected on the island. Battery Gregg was built into the dunes at the northeast tip. Named to honor Confederate General Maxcy Gregg of Columbia, it had three heavy cannons sighted on the shipping channel.

About three-fourths of a mile to the south was Battery Wagner, placed in a narrow section so that it was protected in front by the sea and at the rear by the marsh. Named for Confederate Colonel Thomas M. Wagner of the South Carolina Regular Artillery, it was sturdily built of sand, earthworks, and palmetto timbers. Its walls stood 30 feet high, and its casemate—a fortified gun emplacement—was armed with an arsenal of heavy cannons.

From early July until mid-September 1863, Federal forces attempted to seize Fort Wagner. Union troops numbering approximately 11,000 were supported by its fleet offshore—an armada of gunboats, monitors, and the powerful USS New Ironsides. Wagner was manned by 1,620 Confederates from South Carolina, North Carolina, and Georgia.

The siege of Battery Wagner lasted 58 days and involved two assaults against the fort. Considered one of the great contests in military history, it was a proving ground for radical new techniques: trench warfare, land and sea mines, and the advent of semi-submersibles as well as the submarine CSS Hunley.

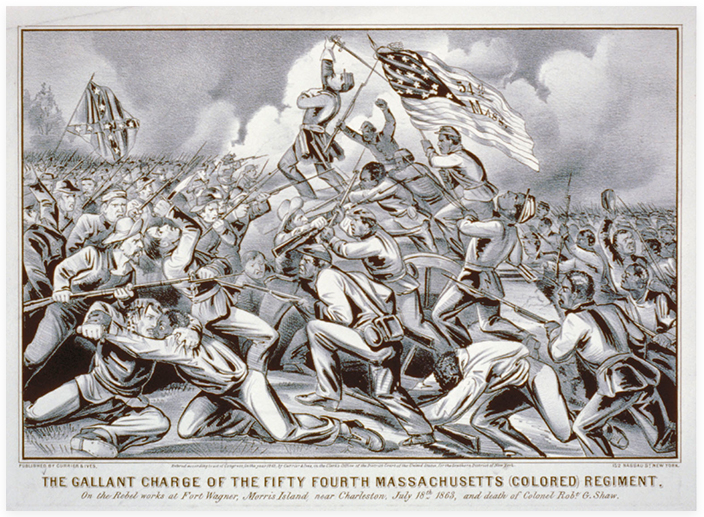

After a failed attempt to take the fort by land on July 10, 1863, the Federals stormed it again on July 18. This ill-fated charge, led by the Massachusetts 54th Infantry (among the first Black regiments to serve), was one of the worst slaughters of the Civil War. Yet the heroism shown by the 54th was lauded by men on both sides and recounted in the 1989 movie Glory.

At sunset on July 18, under the command of the youthful Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the 54th bravely charged the fort at the double quick. Supporting them were the 6th Connecticut and the 48th New York. As they reached the fort, they were hit by a blizzard of shot and shell. Ranks of men were mowed down, and Shaw himself was killed while attempting to breach the parapet. The attack was an unmitigated disaster.

“Language has not the power to describe the horrors of the night succeeding that assault,” wrote Confederate Major Robert Cogdell Gilchrist, who was at Fort Wagner during the battle. “Federal blood flowed by the bucketful. Few could move within that fatal area and live.” The Union counted more than 1,500 in wounded, dead, or missing. The Confederate loss was 174. Most of the fallen were hastily buried in the sand around the fort.

Unable to take Wagner by direct assault, the Union resorted to siege warfare, digging a line of trenches toward the fort while Wagner was bombarded daily from Federal batteries on Folly Island and the warships at sea. Life on the island for both Union and Confederate soldiers became one of unrelenting torment. Aside from the constant barrage, one of the worst challenges was finding fresh water. “Dead bodies were all around,” wrote John Harleston, a Confederate courier on the island. “The water smelt and tasted of them and was half salt anyhow.” Wrote one North Carolina soldier, “I have heard the preachers talk about Hell, a great big hole, full of fire and brimstone…. But Gentlemen, Hell can’t be worse than Battery Wagner.”

The Federals in the trenches faced a more horrific problem. Their digging unearthed the bodies of those killed in previous assaults. Union engineer Major Thomas Brooks reported, “Many soldiers, friends and foe, were wrapped in blankets only, and others not that. As the siege progressed, the scarcity of earth compelled a second, and in one case, a third disinterment of the same corpse.” Nor were all the bodies those of their fallen comrades. Brooks ended with this macabre note: “On an old map, Morris Island is called ‘Coffin Land.’ It was used, I am informed, as a quarantine burying-ground for the port of Charleston.”

Union forces never succeeded in taking Wagner by force. On the night of September 6, both Batteries Wagner and Gregg were secretly abandoned. The Union took Wagner the next day, unopposed. All told, it had cost them 2,318 in dead or wounded to capture the resolute fort.

Now in Union hands, in 1864 Morris Island became as densely populated as ever in its history. The Federals built a supply base and wharf at the south end, and some 10,000 men were bivouacked there.

In August 1864, the island briefly became a prisoner-of-war camp where 600 Confederate prisoners were confined in a one-and-a-half-acre open stockade on the beach directly in front of Battery Wagner. Since Union prisoners were being held in Charleston and the city was being fired upon, the Union command felt that a similar placement of Confederate prisoners in the line of fire was justified.

During the 45 days the prisoners were kept in the pen, three died of starvation. Although 18 shells exploded directly over the stockade and several actually landed inside, miraculously no one was killed. Despite the placement of these human shields, the Confederates never stopped firing, and one Confederate artilleryman quipped, “We simply improved our aim.” For their bravery during captivity, these prisoners became known as the “Immortal 600.”

A Slow & Steady Demise

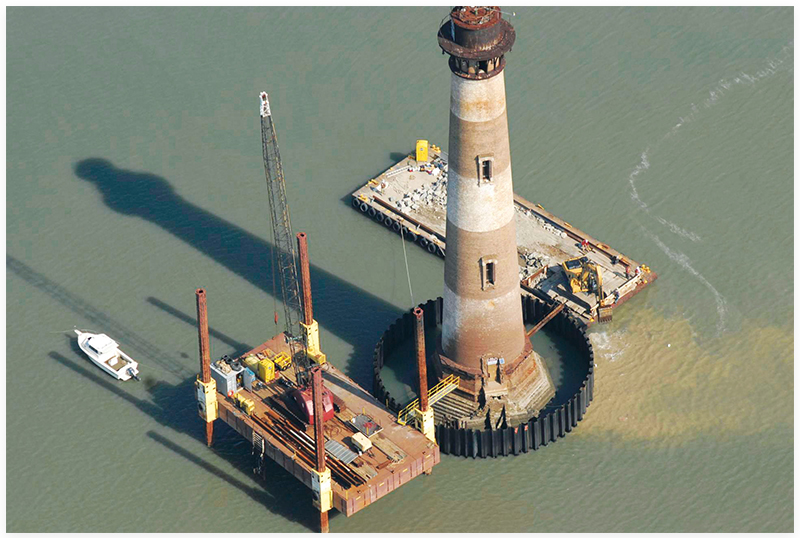

With the lighthouse destroyed during the Civil War, work began in 1873 on a new tower. Illuminated for the first time on October 1, 1876, this is the 158-foot-tall seacoast light with horizontal markings that now stands surrounded by water in Lighthouse Inlet.

At about this same time, work began on the two lines of rock jetties that would form the central shipping channel that leads into Charleston Harbor. As a stopgap to erosion, spurs from the main jetties were to be extended to the beaches of Sullivan’s and Morris islands. The spur to Morris, however, was never completed. This, coupled with the severe back-to-back hurricanes of the late 1880s, caused the island to begin eroding at an alarming rate. Once again, the dead buried on Morris Island would have no rest. The lightkeeper at the time reported that after every storm he would fill a wagon with the unearthed bones for reburial.

By the turn of the century, only the outline of Battery Wagner remained. By the 1930s, the lighthouse was at the water’s edge, and the lightkeepers’ house was practically underwater. Today, the lighthouse stands a half mile offshore.

Indeed, what remains of Morris Island is hallowed ground. It’s impossible to say how many have been buried on the island since it was given the name Coffin Land. From shipwrecks, disease, and war, this barrier island has perhaps received more dead than any other place in South Carolina. Erosion continues to eat away its shores, but the history made here cannot be washed away.

(Clockwise from top left) Schoolteacher Elma Bradham traveled by boat to Morris Island every Monday, living with the lightkeepers’ families and teaching the children. On Friday, she returned home to John’s Island; The Davis and Hecker families on the beach at Morris Island, circa 1935; Lightkeeper Ed Meyer’s Ford Model T, which he moved to Morris Island in 1934 by precariously resting it atop three rowboats.

Morris Island wasn’t always bloody battles and hasty burials. Indeed, people and other living creatures thrived there from the 1870s to just before World War II, when a succession of lightkeepers and their families called it home. >>READ MORE

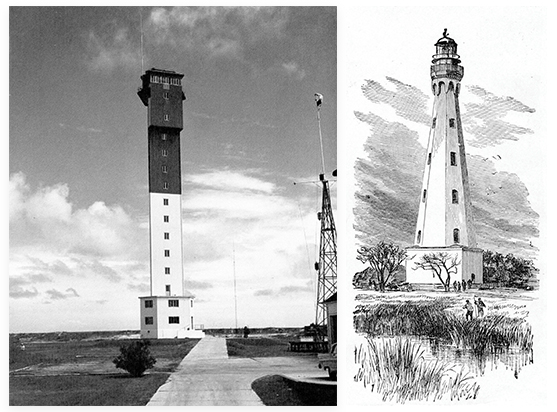

(Left to right) The Sullivan’s Island Lighthouse; the second lighthouse on Morris Island, built in 1801.

The evolution of the Morris Island Lighthouse >>LEARN MORE HERE

After a failed attempt to take Fort Wagner by land on July 10, 1863, the Federals stormed it again on July 18. Led by the Massachusetts 54th Infantry and depicted in the above print. The heroism shown by the 54th was lauded by men on both sides and recounted in the 1989 movie Glory.

When Confederate forces evacuated in September 1863, Union troops quickly built dozens of barracks, gun emplacements, supply depots, and a wharf. By 1864, some 10,000 troops were stationed on the island >>READ MORE

Local advocates and preservationists band together to save the island and its historic light

While Morris Island continues to erode (it is now classified as a “roll over” barrier island, ie, the entire island can flood given tide and weather conditions); what little high ground and history remaining has been preserved, thanks to a cooperative effort between a variety of public entities and private individuals. >>READ MORE

Photographs by Jon Puckett; courtesy of Douglas W. Bostick; courtesy of Library of Congress; Andy Lassiter; Richard L. Beck; from the Colonel Peter C. Hains collection; from the Faith Ferguson collection; from the Katherine Davis Craig collection, courtesy of Douglas W. Bostick; from the Mrs. Roulain Deveaux collection, courtesy of Douglas W. Bostick; Richard L. Beck; (Lighthouse rendering & Sullivan’s Island Lightouuse) courtesy of Douglas W. Bostick; courtesy of Taylor Bros. Marine Construction, Inc.; Photograph from the Jim Booth collection; from the Katherine Davis Craig collection courtesy of Douglas W. Bostick