As a downtown bookstore owner, I’ve found the repetitive nature of retail work lends itself to predictable conversational patterns. Since opening three years ago, I’ve acquired some banter as automatic as computer macros, like: “Can you sign this copy for me?” or “Just down the hall and to the left.”

My first job was bagging groceries at Harris Teeter, back in the glory days of a classic: “Paper or plastic?” In Charleston, working retail or waiting tables or any other job that interacts with the public equals tourists. And that means being thrust into the tricky role of concierge, tour guide, traffic cop, and ersatz representative of the city’s more than 300 years of tradition—and language.

The vast majority of visitors are wonderful and curious and patient, but there are those who would prefer I speak like Rhett Butler and maybe put my hands on the opposite knees and give ’em a few steps of The Charleston. For example, I get this a lot:

“Where are you from?”

“I’m from Charlotte,” I say.

“You don’t have an accent.”

“The South is a big place.”

It’s the macro I plug in whenever I get the accent question. I really don’t know how else to answer it. It’s not the fault of Northerners. The fact is, most Southerners know that accents range widely from Arkansas to Virginia to Northern Florida, and often what you hear on TV and in movies is none of the above.

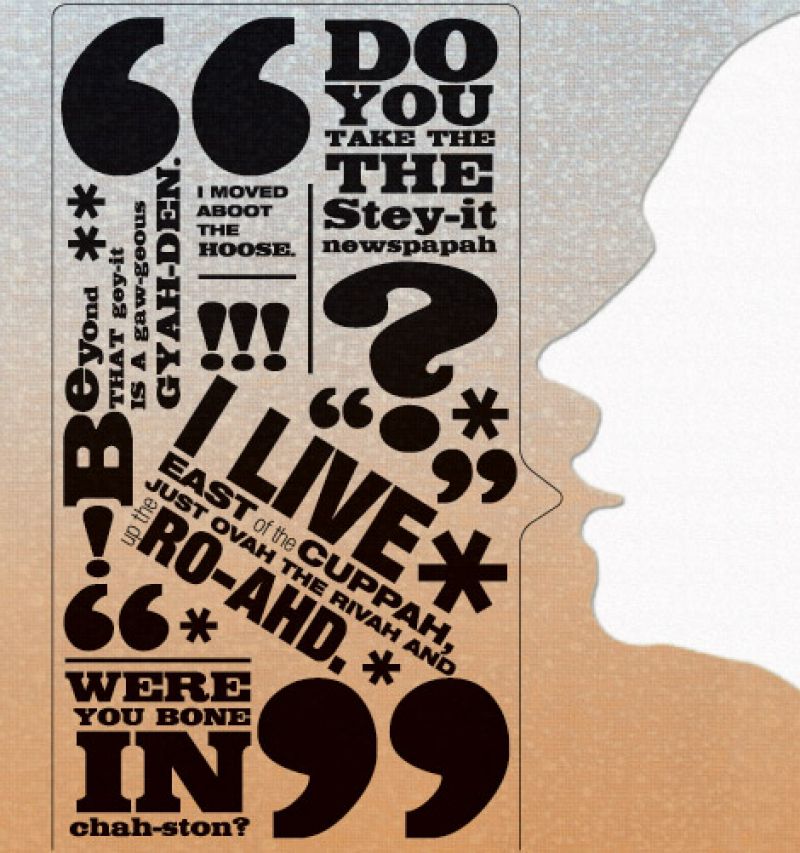

The Charleston accent is one of the things I’ve come to love about the Lowcountry. It’s a low sound. I think of the way people talk in Columbia and Charlotte as higher, coming from the top of the palate and nasal passages. The Charleston accent seems to come from the bottom of the mouth, the jaw jutted just a bit, the lips a little pursed. Cooper becomes “cuppah,” house is “hoose,” and state, “stey-it.”

My wife and I used to attend Sacred Heart Catholic Church on King Street, north of the Crosstown. The tiny parish is a vestige of the Greek, Irish, and Lebanese immigrants who built the Wagener Terrace and North Central neighborhoods in the first half of the 20th century. Many of the parishioners have Charleston accents that to the untrained ear almost can’t be placed—sort of like that New Orleans accent that could be straight out of the Bronx. An old Charlestonian could say, “I moved aboot the hoose,” and you might think she was from Toronto.

I don’t have the space nor the credentials to delve into the glories of Gullah; there are entire books for that. But I do love to correct friends from out of town who think they met a Jamaican selling vegetables on Folly Road. The number of full-blown speakers of the Gullah language on Wadmalaw Island or America Street or elsewhere in the Lowcountry may be in decline, but I’m happy to say that Gullah-inflected accents are carrying over into the next generation—like the young people at Burke High School who call me “Musta Sanchez.” But I worry that the accent of white Charlestonians will not endure as long as the single house.

Bill Bryan, a regular in my store, wrote for the old News and Courier for years. He likes to talk about the zoo that used to be in Hampton Park or King Street when it had all the neon signs and a different movie house for every type of movie—one known for Westerns, one for B movies, and so on. He has a textbook Charleston accent. Lyrical and low, it’s as different from Andy Griffith’s as purloo is from smoked brisket. Bryan says that when he first started school at USC, his classmates from the Upstate would often ask him to say “I take The State paper.”

I love the Charleston accent because it’s unique and strange and still reflects the unique and strange old-world influences of the city. It’s living proof that in some ways Charleston is still tied to the Eastern Hemisphere and has not assimilated to the rest of the country. It seems fragile and fleeting, only a matter of time before you would never dream of people living 100 miles away in the same state—or “stey-it”—speaking differently.