A few ages ago, I sat on a curb waiting for a friend. This was pre-cell phone era, so there were no easy distractions to bide my time, and I remembered a curse my Danish mormor (grandmother) had passed unto me as a 10-year-old: “Intelligent people,” she said, “are never bored.” Lingering on that sidewalk edge a decade later, her adage revisited me, this time birthing a game that I now play whenever I am at risk of being “unintelligent” or am just plain unsettled. As a sort of mental fire escape, I try to imagine all the people who have touched the very spot I’m on. I go as far back as I can until life resets, the ho-hums abate, and my place in a bigger world is right again.

The game popped up recently when I was running morning loops around the track inside Hampton Park and noticed an odd box tacked onto the concession stand near the lagoon. It had not been there the day prior, so I asked what-gives to Richard, the city landscaper who tends to the beds there; he said it was Wi-Fi and that the structure was being rehabbed into a working food stand. New bathrooms. Little tables. A short fence to hug it all. Charm in spades.

Logically, I was horrified. It was the C word—“change”—that got me.

I kept on looping, trying to breathe through my oddball reaction. Clearly I’ve become attached to this bit of land, its rhythms and its patchwork of elements. Years ago, I would defy posted warning signs and pet the police horses in their paddock. I still gooberly wish the uniformed kids walking through the park a great day at school, and I felt I was one with the neighborhood when the pre-dawn pack of retirees dubbed me “girlfriend” and noticed if I’d missed a day. Then there’s the ever-expanding flock of resident ducks and the epic bounty of blooms that bud, flourish, fade, and drop month after month, season after season.

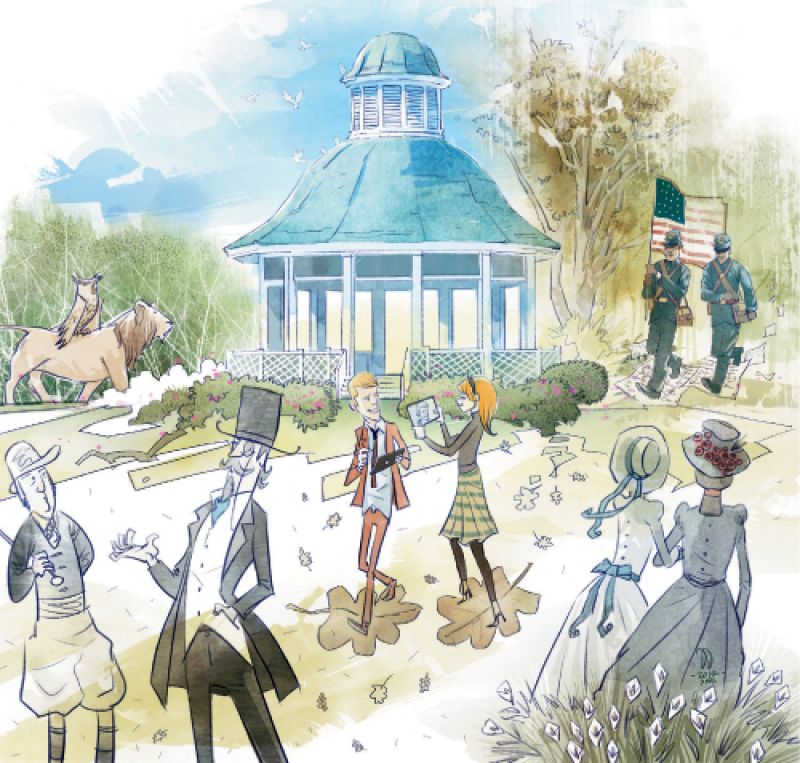

And yet, there I was hung up on a small metal box, shaking my fist at it like a grumpy old man. I’d felt the same way when an army of enormous power poles was installed across the park last summer—their crackling and humming, the buzz of modern life, was just what I came to the park to escape. So the unrest brought back the time-travel game. Thanks to having read Kevin Eberle’s A History of Charleston’s Hampton Park and heard stories from Holy City old-timers, I mentally flipped through the chapters of the park’s life. As recently as the 1970s, it had hosted a zoo. From 1901 to 1902, it had been the site of the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition, with glorious Spanish-Neoclassical halls at every turn. In the 1860s, it had been an internment camp for Union prisoners, eventually a burial ground for them, and, after the Civil War’s end, the site of the reunified country’s first Memorial Day celebration. Before that, a Colonial-era racecourse with a grandstand had stood there. And pre-racing, it had been a plantation land, and on, and on, and on.

The game, by nature, is humbling and this time pushed me to ask who in the world was I to begrudge yet another shift, especially one that could ensure the life and liveliness of a cherished public space? If not for the passage of time, its oak allée wouldn’t have grown into a canopy. And surely, if not for time and change, the powerful Denmark Vesey statue wouldn’t have been erected here last year.

My neighbor Geneva and I were recently talking about all these shifts. (She grew up on Kennedy Court until the Crosstown practically cut her backyard in half. Before I moved onto Race Street almost a decade ago, I went door-knocking to gauge the friendly factor and found her to be a grade-A welcome wagon.) A hipster dad walked by us pushing a baby jogger and nodded. After he was out of earshot, I said how strange that was, meaning all the young white families that have moved in (before, I used to only see other white folks during the Greek Festival or for Greek church). Geneva chimed in that it was certainly weird. “When my children were young,” she said, “men never talked about their kids, let alone went around pushing baby carriages.” Looking at the very same thing, we were reading different chapters in time.

If you walk across the Crosstown at the Rutledge Avenue intersection and pause at the median—just for a moment, given the location—you’ll see a quote by Charleston civil rights activist Septima P. Clark carved into the stone border. It reads, “The only thing that’s really worthwhile is change. It’s coming.” What a curious conflux of sentiment, personality, and place. All on another little curb in another little corner of a little city in a big, big world.