The managing partner of Indigo Road lays it all on the table with his forthright memoir

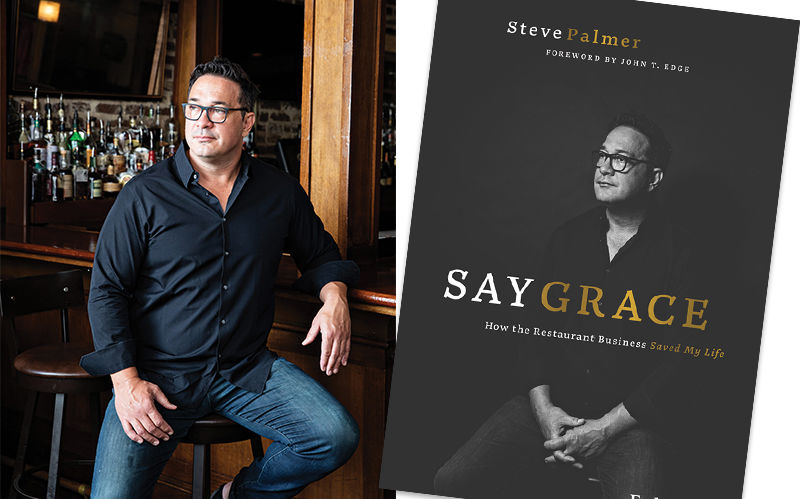

(Left) Steve Palmer is the managing partner of The Indigo Road Hospitality Group, which owns and operates restaurants in four states; (Right) Restaurateur Steve Palmer recounts growing up as a homeless addict and how he forged a path to recovery while working in the restaurant business in his memoir Say Grace, which was published in October.

Alcohol and the bleak depths of addiction are at the forefront of Steve Palmer’s book Say Grace: How the Restaurant Business Saved My Life (Forbes, October 2019), but don’t be fooled: This is a story about family—with all its inherently messy complications and deep connections.

These days Palmer is best known as the managing partner of The Indigo Road Hospitality Group, which is to say he’s a savvy restaurateur with a Midas touch, first taking over at Oak Steakhouse, then opening and operating a succession of heralded enterprises that include O-Ku, The Macintosh, and Indaco. But his path to success was not always a direct one. The Atlanta native and former Fuddruckers line cook was once a homeless 16-year-old cocaine addict who stole food from corner markets. Palmer writes that he felt his mother “was always trying to pawn me off on someone else.” By the age of 17, he’d jumped from an abusive treatment facility to a Christian youth shelter to a 12-step recovery program in Tennessee that helped him get sober—at least for a little while.

Say Grace chronicles a familiar tale of wayward youth and reckless substance abuse, but Palmer recounts his less-than-pristine past with a clear-eyed reckoning, demonstrating how easily one can end up on a harrowing trajectory. He hoped for a fresh start in 1990 when he relocated to Charleston, where his sister lived. However, the drugs and alcohol started over here, too. With no college degree and little experience, Palmer landed a job as a resort bartender, and this early taste of the food and beverage world marked the first time he experienced “unconditional love and acceptance” in the close relationships he had formed. His newfound interest sparked an enduring passion for the restaurant industry—sadly one ravaged by substance abuse.

Palmer counts himself among the lucky ones. Despite his alcohol and drug addiction, he eventually worked his way up to the highest echelons of Charleston fine dining (the book offers a nostalgic romp through the city’s culinary evolution, back when French Quarter restaurants reigned). Peninsula Grill owner Hank Holliday saw Palmer’s strengths and potential and issued an ultimatum that saved his life.

In Say Grace, Palmer exposes the “duality of the hospitality industry,” full of “the most caring people you will ever meet” who work hard and party harder, but who “often fail to take care of themselves.” With the support of peers and family, Palmer learned how to stay sober in an industry fueled by wining and dining. But he didn’t stop there. Along with Charleston Grill’s Mickey Bakst, Palmer founded the nonprofit Ben’s Friends to help support those in the food industry fighting addiction. “We can’t keep losing people to overdoses, to burnout, to alcoholism, to suicide,” he writes. Palmer is a wizard at creating enticing restaurants that welcome people and serve them food for the soul. By sharing his story in Say Grace, he extends a beacon of hope to anyone struggling to right their own path.