Clemson University’s Cooperative Extension shares tips and plans for easing flooding and erosion in local landscapes.

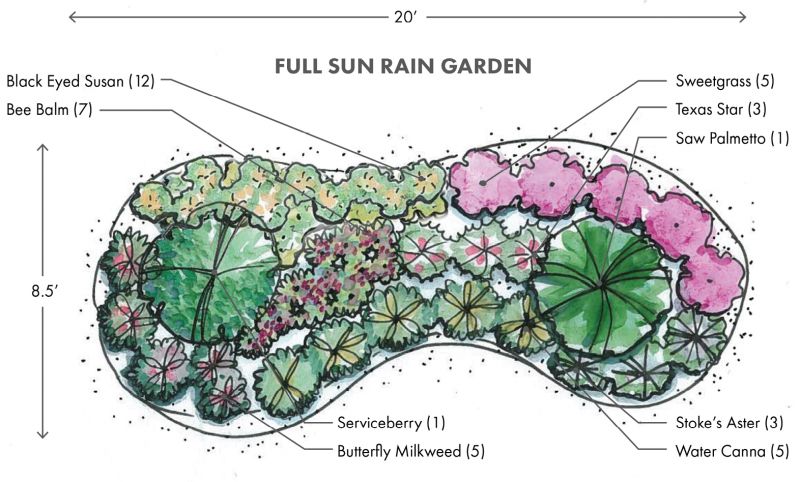

Clemson Extension’s “A Guide to Rain Gardens in South Carolina” publication includes sample designs like this full-sun option.

“Everyone is thinking about water and how to manage it,” says Kim Counts Morganello, a water resource agent with Clemson University’s Cooperative Extension. Each year, more locals call with questions about easing flooding and erosion in their landscapes.

One answer: plant a pocket rain garden. These beds are actually “landscaped depressions” filled with native plants that don’t mind getting their feet wet.

“A rain garden allows water to slow down and infiltrate into the ground,” explains Morganello. Its shape, together with the plants and soil, helps to filter out pollutants (like excess fertilizers) that may otherwise run off into the surrounding environment or flow into waterways via storm drains.

To walk homeowners through creating this beneficial feature, Morganello and her Clemson cohorts created the Carolina Rain Garden Initiative, which includes free resources such as “A Guide to Rain Gardens in South Carolina” and video tutorials. (And for those who’d rather call a pro, clemson.edu/extension/raingarden also lists installers certified through the Master Rain Gardener program.)

(Left to right) Bee balm feeds butterflies and hummingbirds; black eyed Susan adds color to the garden and makes a great cut flower.

Your first step? Find a location. “A rain garden isn’t for that place in your yard that’s always soggy,” says Morganello. “In fact, it will be dry more often than it is wet.” On a stormy day, watch how water flows across your property—the bed should intercept runoff from a roof, driveway, or sidewalk.

Once you have your eye on an area, call “811” to identify any buried lines or cables. Then do a percolation test: dig a six-by-six-inch hole and fill it with water. If it drains in 24 hours or less, you’re good to go.

Clemson’s resources can help you determine your bed’s size based on the impervious surfaces impacting it; a design just eight to 10 feet long often does the trick. To create the depression, dig out 10 or so inches of earth, banking some of it into a berm along the downstream edge. Then amend the garden’s soil with compost and perhaps sand (again, Clemson advises on finding the right mix).

Saw palmetto adds evergreen interest.

Finally, it’s time to plant. “Native species will perform best,” notes Morganello. “And they create habitat for songbirds and pollinators.” You can marry grasses, perennials, ferns, and shrubs into a mini haven that’ll benefit more than your personal landscape. “If more residents take ownership over the water that falls on their property by creating rain gardens, we can collectively help reduce area flooding and protect local water quality,” says Morganello.