The Black House shines a spotlight on contemporary art and architecture

Ask a child to draw a house, and you’ll get three straight lines with a gabled roof on top, two big windows, and a door, sort of in the middle. Most any parent has seen and treasured one, but when architect Kevan Hoertdoerfer saw his daughter’s hand-drawn house, he decided to bring it to life.

The Charleston-based architect was in the midst of renovating a 1950s cinder-block home in the Wagener Terrace neighborhood when his clients—designer Karen Baldwin and her partner, who invests in creative projects—told him about a double-sized lot two doors down that they had purchased. The couple wanted to replace the duplex there with two modern houses. “We were all standing there, talking about contemporary design, and as a group we wanted an unbiased, naive answer to a very simple question,” says Hoertdoerfer. “So, we asked my daughter Sadie, who was 11 at the time and the youngest one in the group, to draw us her idea of a simple contemporary house.”

Fast forward three years and the two story, 2,740-square-foot home bears a strong resemblance to that original drawing, albeit wrapped entirely in black metal with walls of glass. “The Black House,” as it is often called, is a striking, contemporary structure, bold in its simplicity and surprising in its complicated relationships with space, color, and shape. “The concept was to take that very traditional profile of the house and make it as contemporary as possible,” says Hoertdoerfer.

Baldwin and her partner wanted a four-bedroom, two-and-a-half-bath house with an open floor plan and big windows to take advantage of the southern light and the view of Hampton Park. Beyond that, she says, “We trusted Kevan’s design instincts implicitly.”

Stepping inside, the dramatic black exterior—a combination of a standing-seam aluminum roof brought down the sides and shiplap siding on the front and back—gives way to a home filled with white and light. “Essentially, we created a blank canvas for bigger pieces of artwork and a broader range of interior pieces,” says Hoertdoerfer, referencing Baldwin’s collection of contemporary art, including an original Andy Warhol screen print that hangs in the living room. “With the exterior being black and the interior white, you end up with the simplest of palettes, allowing you to do pretty much anything you want on the inside,” he says.

The first-floor living space is largely uninterrupted from the floor-to-ceiling front windows overlooking Hampton Park to their counterpart in the rear. A few architectural and storage elements—a small powder room, kitchen pantry, entry closet, and open stairwell—offer enough nuance to keep it from feeling like one big box. Toward the back, the kitchen, with a large island, helps partially divide and separate the space, while simultaneously connecting everything. A central stairway, laid with whitewashed end grain Douglas fir, is a warm transition from the epoxy floor. It leads to the second-floor bedrooms via an enclosed stairwell, with windows through which light plays with the home’s angles.

The artistic origins of the home are not the end of its creative story. Baldwin, an artist herself, is a supporter of the city’s contemporary art scene. “We loved the idea of showcasing local artists in the house as part of a continued ‘home is art’ concept,” she says of their collaboration with nearby Redux Contemporary Arts Center, hosting a fundraising event for the nonprofit. “We just fell in love with some of the pieces, so they’ve stayed,” she says. Netflix, a large oil painting by Karen Ann Myers hangs above the Normann Copenhagen dining table (purchased from IOLA in Park Circle), Jonathan Rypkema’s pastel wood panels lure visitors up the staircase, and Carey Morton’s Beast of Burden sculpture guards the front door. Baldwin also commissioned an outdoor mural by McKenzie Eddy and Elliott A. Smith, local designers and artists known for their big, bold creations. The burst of white circles on the black metal siding is called Cosmic Stars.

The collaboration with Redux, which began with Baldwin and her partner’s first home, also led to the start of a contemporary art and architecture outreach program with James Simons Elementary School. Called “Home Is Art,” it started with Hoertdoerfer asking a group of first through fifth graders the question, “What is architecture?”

“Kevan used photographs and models of contemporary architecture to illustrate that architecture can be anything,” explains Redux executive director Cara Leepson. “The kids ran with the prompt and really embraced the idea that a home can be in any shape or form.”

The shape and form of The Black House—as well as Baldwin’s first project with Hoertdoerfer with its prominent, angular silver roof—have raised a few eyebrows in a town accustomed to traditional styles. “A group of people walked by the other day, and I heard one of them say, ‘What is this? The contemporary architecture street in Charleston?’” says Baldwin. For both her and Hoertdoerfer, bringing modern design into this historic city has been rewarding. “There’s been an emergence of modern architecture in the last five years,” says Hoertdoerfer. “It goes hand-in-hand with Redux moving into its new space and having more contemporary art galleries, contemporary theater being more prevalent, and a broader range of culinary experiences in town.”

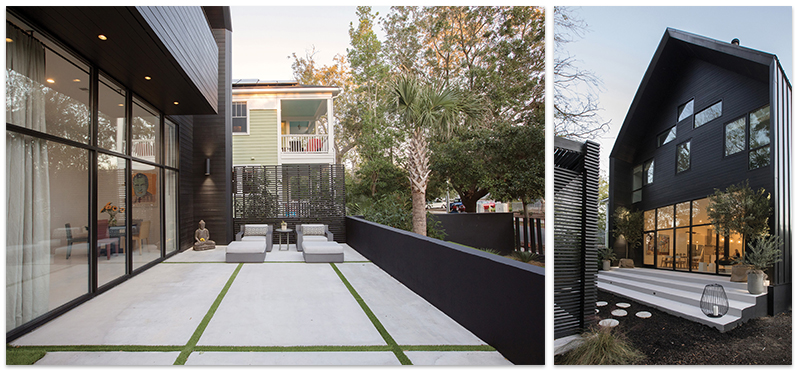

(Left) The front patio strikes a contrast with the traditional porch behind it. Artificial turf between large concrete pavers soften the space, adorned by two Restoration Hardware lounge chairs. (Right) In the back, long, deep steps lead to the cabana where Hoertdoerfer’s window configuration can be best viewed. “The easy thing would have been to just make it a wall of glass,” he says. “But that wouldn’t relate to the program on the inside, so we played with patterns and forms and lines to find something that made sense from a compositional, as well as a functional, standpoint.”

Hoertdoerfer, paying homage to the progressive architects who came before him—such as Ray Huff, Reggie Gibson, and Clark and Menefee—points out there are many hidden gems of contemporary architecture in this city, and that it feels like there’s more exposure, acceptance, and excitement for it. “I think there is a strong desire to have the full range of architectural styles in this town,” he says.

Not that The Black House has been without its critics—but that conversation, including the fact it is just beyond (by mere yards) the purview of the city’s stringent Board of Architectural Review, is all part of creating a dialogue around contemporary art and architecture. “My approach has always been that good design matters, regardless of the style or the historical framework,” says Hoertdoerfer. “To design a quality structure, it needs to respond to its site, its context, and the history of the place it’s located.”